Oct. 15, 2019

Maxime Bernier either doesn’t know or doesn’t care that immigrants have a positive impact on the economy

The anti-immigration rhetoric heard on stage at the national leaders’ debates may have surprised many Canadians. Calls from the political fringes for major immigration reform to preserve or restore some imagined character of the state has been a trend in other western industrialized democracies like France, the Netherlands and the United States, but up till now, has been absent in mainstream Canadian political discourse.

The emergence of immigration as an election issue in Canada is due largely to the country’s newest political party, The People’s Party of Canada (PPC), which was formed in 2018. For the PPC and its leader Maxime Bernier, immigration is a core issue and forms a major component of the party’s election platform.

While the PPC relies heavily on populist rhetoric — for example, opposing Canada’s supposed “cult of diversity” — its platform does try to provide an economic rationale to support both a drastic reduction in the number of immigrants admitted to Canada each year and a shift in the criteria used for deciding who gets in.

It is a curious position to take for a party that wants to form government, given that a recent poll finds the majority of Canadians support immigration — either keeping immigration levels as they are or increasing them. But it is a position that has found some supporters, if only at the relative fringes of Canadian politics, and has been politically successful in other countries known historically to be open to immigration.

There is a compelling case for not providing a space to air the ideas of Bernier and the PPC. But the federal Canadian debate commission allowed his participation in the two national debates, so the ideas are out there and demand a critical analysis. In particular, careful attention should be paid to separating fact from fiction, given the way fringe anti-immigration politics have successfully infiltrated other western democracies.

Misunderstanding or misinformation?

The economic rationale provided by Bernier and the PPC belies either a fundamental misunderstanding of the economics of immigration, or worse, an unabashed attempt to stoke anti-immigrant sentiment for political ends.

The PPC’s platform begins by saying that immigrants “should not put excessive financial burdens on the shoulders of Canadians….”

This is a commonly used justification for tightening immigration. It is intended to create the impression that immigrants receive a high level of benefits relative to other Canadians, and that the economic cost in terms of taxpayer-funded government benefits received by immigrants outweighs the economic benefit in terms of income tax paid.

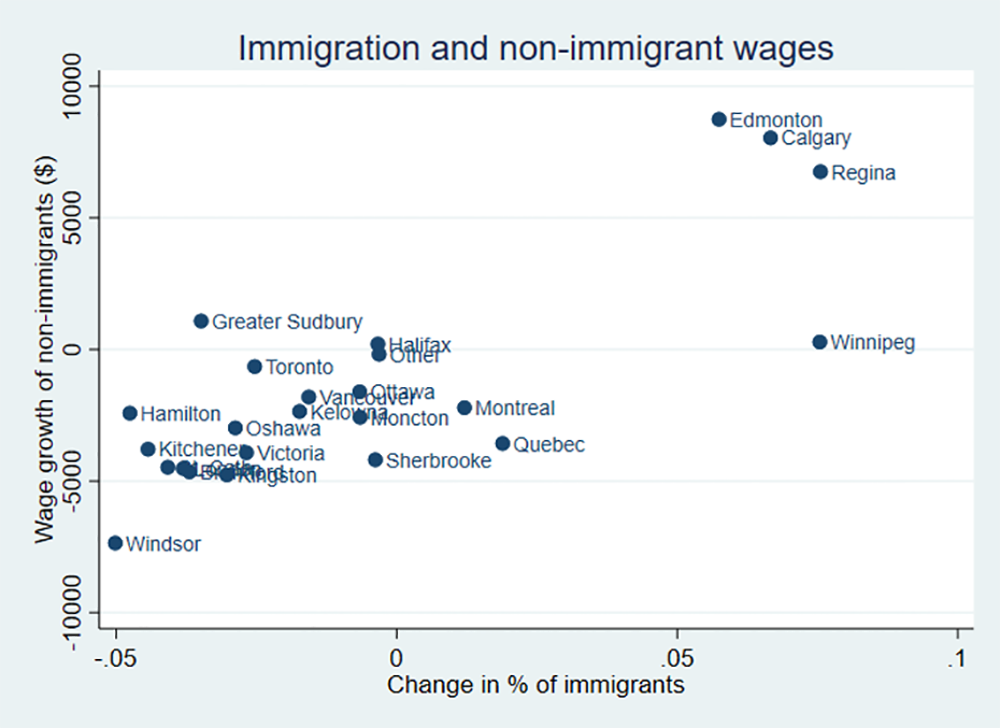

Wage growth of non-immigrants and changes in immigrants per capita in Canada’s largest cities

Using the latest available data from the 2016 census, we can calculate average benefits received and taxes paid for immigrants and other Canadians.

The truth is, the average Canadian immigrant does not receive more government benefits than the average non-immigrant and the average immigrant to Canada did not “cost” more than they paid in taxes.

The total amount of government transfers received by the average Canadian immigrant was $7,776.80, while the total income tax paid by the average Canadian immigrant was $10,803.73. The numbers for the average non-immigrant Canadian citizen were $7,891.86 and $12,610.88 respectively.

In its platform, the party states non-immigrants pay more in income tax than immigrants, which is supported by the data. The reason, as the platform also correctly suggests, is that non-immigrants have higher labour market earnings than do immigrants. However, the children of immigrants — second generation Canadians — end up earning more and paying more taxes than the average non-immigrant Canadian.

That immigrants earn less than non-immigrants is neither news nor a surprise. The immigrant wage gap is a well-documented phenomenon , and much research has been devoted to understanding its source.

Highly employed and educated

The PPC’s platform implies that immigrants earn less because they do not offer the same value to the economy as a non-immigrant. The suggestion is that immigrants are supposedly less likely to be employed or are simply paid less to reflect their lower market value.

In reality, Canada’s immigrant employment rate, at 92.4 per cent, is actually on par with (or marginally higher than) the non-immigrant employment rate at 92.3 per cent. Second, the education level of a typical immigrant is higher than that of the typical non-immigrant.

As one example, the census data shows the typical immigrant is 40 per cent more likely to have a bachelor’s degree than a non-immigrant.

The fact that immigrants are just as likely to be employed and have a higher level of education than other Canadians while earning less perhaps says more about the functioning of the Canadian labour market than anything else.

Problems with recognizing and understanding foreign credentials and work experience or even simple labour market discrimination have both been identified as issues in the Canadian labour market.

Well-functioning economies are characterized by high labour mobility —workers being willing and able to move from one region to another for economic opportunity.

Another way immigrants play an important role is that they are four times more likely to have moved provinces in the five years leading up to the 2016 census than are non-immigrants. Canada’s economy is a collection of industries that in some cases are regionally concentrated. As such, there are often labour shortages in one region of the country and high levels of unemployment in another.

Immigrant labour supports non-immigrant labour

One particularly divisive claim that is often made by anti-immigration populists is that immigrants are bad for non-immigrant labor outcomes. But recent studies that have looked at the effect of immigrants on non-immigrant wages and well-being have found evidence of positive effects in both cases.

Using the 2016 and 2006 census data, we can look at the relationship between immigrants per capita and non-immigrant wage growth in Canada’s largest communities over a 10-year period.

A scuffle breaks out before a People’s Party of Canada election event in Hamilton, Ont. on Sept. 29.

The pattern is striking — metropolitan areas that experienced an increase in immigrants per capita also experienced growth in the wages of non-immigrants. This should not be read as a causal relationship. Being more willing to move provinces, immigrants “equilibriate” local labour markets by leaving low wage/low opportunity locations for high wage/high opportunity ones, which at least partly explains the pattern.

But there is economic logic for why more immigrant labour can increase wages for non-immigrants — immigrants often do jobs that are complementary to, as opposed to a substitute for, the jobs that non-immigrants do.

Trump has praised Canadian system

The PPC immigration platform includes a call to reform Canada’s immigration system in an echo of the the Trump administration’s repeated call for a switch to “merit-based” immigration in the U.S. Ironically, Trump cites Canada as a shining example of such a system.

This call asks immigrants to be selected based on “economic class” and their skills (education, work experience, language) as opposed to the “family class” that exists primarily to reunify families of immigrants.

The PPC platform claims that only 26 per cent of immigrants to Canada come through the economic class. This is factually incorrect.

The 2017 Annual Report to Parliament on Immigration states the majority of immigrants to Canada (53 per cent) already come through the economic class, which is likely why Canada’s system is envied by the Trump administration.

In any case, the PPC is also wrong to claim that entrants through the family class take more from the system in terms of government transfer payments than they pay in taxes. The census data reveals that immigrants who entered through the family class pay an average of $8,231.28 in income tax, while receiving $6,665.73 in government transfers.

Further, though immigrants through the family class are not selected specifically for their economic value, they often provide key services like free child care for immigrant parents. There is robust evidence that free childcare has large effects on maternal labour supply, which of course ultimately means higher taxes paid by immigrant parents.

Ultimately, the case for immigration reform as envisioned in the PPC platform cannot be an economic one. As such, Bernier and his PPC should not be so surprised when they are accused of xenophobia and racism by the media and other political parties.

Like what you’ve read? Want more? Sign up for The Conversation’s daily newsletter.